The first matter which calls for the student’s special attention is the proper production of the tone. This is the basis of all good execution; and a musician whose method of emission is faulty will never become a great artist.

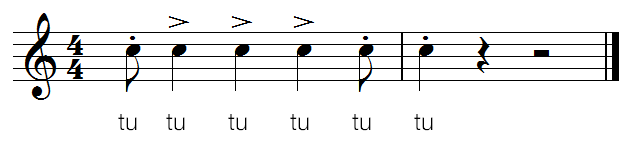

In the Piano as well as the Forte, the “striking” or commencing of the sound ought to be frank, clear, and immediate. In striking the tone, it is necessary always to articulate the syllable TU, and not DOUA, as is the practice with many executants (players). The last mentioned articulation causes the tone to be taken Flat, and imparts to it a thick and disagreeable quality.

The proper production of tone having been duly arrived at, the executant should now strive to attain a good style. I am not now alluding to that supreme quality which is the culminating point of art and which is possessed by so few artists, even among the most skillful and renowned, but to a less brilliant quality, the absence of which would check all progress, annihilate all perfection. To be natural, to be correct, to execute music AS IT IS WRITTEN, to phrase according to the style and sentiment of the piece performed, these are qualities which surely ought to be the object of the pupil’s constant research: but he cannot hope to attain them until he has rigorously imposed upon himself the strict observance of the VALUE of each note. The neglect of this desideratum (prerequisite) is so common a defect, especially among military bandsmen, that I think it necessary to set forth the evil arising therefrom; and to indicate, at the same time, the means of avoiding them.

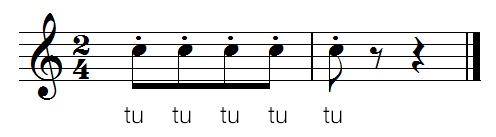

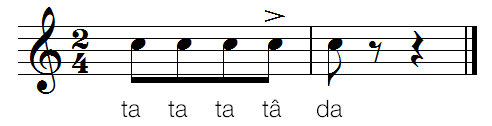

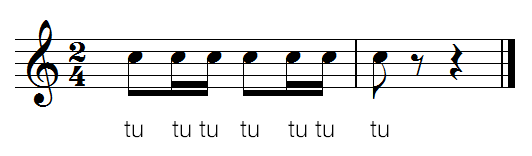

For instance, in a bar (2/4 time), composed of four eighth notes which should executed with perfect equality by pronouncing:

performers often contrive to prolong the fourth note by pronouncing:

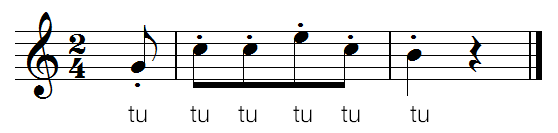

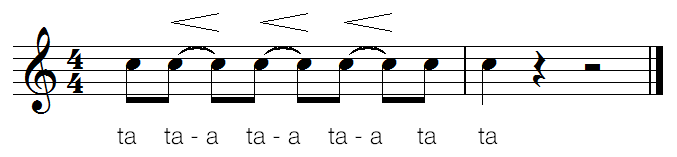

If in this same rhythm, a phrase commences with an ascending note, too much importance is then given to the first note, which has, in fact, no more value than the others. It should be executed thus, each note being duly separated:

instead of prolonging the first note, as follows:

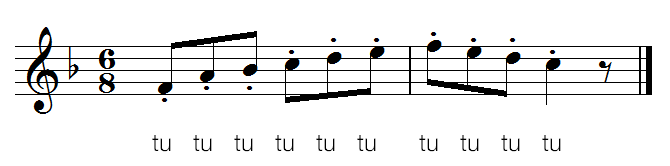

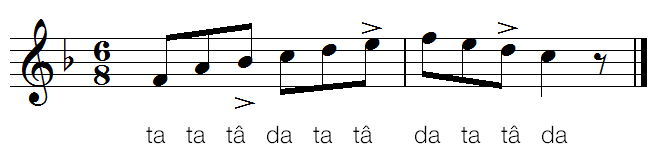

In 6/8 time, the same errors prevail. The sixth note of each bar is prolonged, nay, the entire six notes are performed in a skipping and uneven manner. The performer should execute thus:

and not thus:

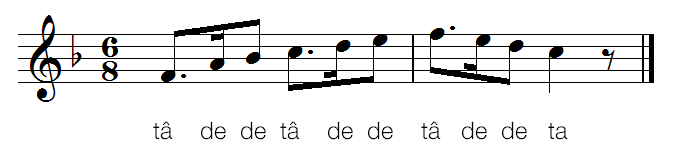

Other artists again, execute as though there were dotted eighth notes followed by sixteenths:

The reader will now perceive, from the preceding remarks, how prejudicially a bad articulation may influence execution. It must even be borne in mind, that the tongue stands in nearly the same relation to brass instruments, as the bow to the violin; if you articulate in an unequal manner, you transmit to the notes emitted into the instrument syllables pronounced in an uneven and irregular, together with all the faults of the rhythm resulting therefrom.

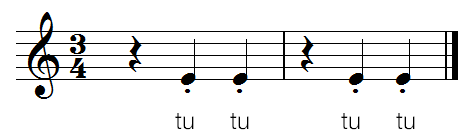

In accompaniments, too, there exists a detestable method of playing in contra-tempo. Thus in 3/4 time, each note should be performed with perfect equality, without either shortening or prolonging either of the two notes which constitute this kind of accompaniment. For instance:

instead of playing, as is often the case:

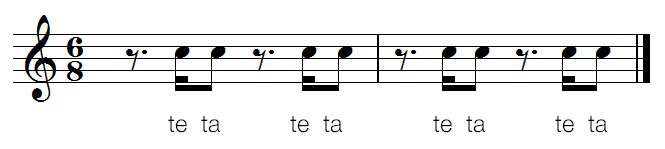

In 6/8 time, there exist an equally faulty method of executing the contra-tempo. This consists in uttering the first note of the contra-tempo as though it were a sixteenth note, instead of imparting the same value to both notes. The performer should execute thus:

and NOT as indicated in the following example:

In the execution of syncopated passages, there also prevails a radical defect, especially to be found among military bandsmen; it consists in uttering the SECOND half of the syncopated note.

A syncopated passage should be executed in pronouncing thus:

and NOT thus:

There is no reason why the MIDDLE of a syncope should be performed with greater force than the commencement of the same note. The great requisite consists in causing its starting point, so to speak, to be distinctly heard, and in sustaining the note throughout its entire value, without inflating it towards the middle.

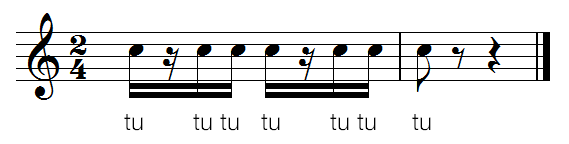

The following illustration must be executed with mechanical equality, by pronouncing without pressing:

It must, moreover, be observed, that the first eighth note should be separated from the two sixteenth notes as though there were a sixteenth rest between them. For instance:

and NOT, as is but too often the case, by dragging the first note, and producing a bad coup de langue, viz:

The student will, later, learn to execute the same passages in coup de langue, but the tongue must, first of all, be trained lightly to express every species of rhythm, without having recourse to this kind of articulation.

Besides the faults of rhythm which have just been pointed out, there exist many other defects, almost all of which may be attributed to ill-directed ambition, doubtful taste, or a lamentable tendency to exaggeration. Many artists imagine that they are exhibiting intense feeling when they swell out notes by spasmodic fits and starts, or indulge in a TREMOLO produced by means of the neck, a practice which results in an “OU, OU, OU” of a most disagreeable nature.

The oscillation of sound (vibrato) is obtained on the cornet, as on the violin, by a slight movement of the right hand. The result is highly sensitive and effective; but care must be taken not to indulge in this practice too freely, as its too frequent employment becomes a serious defect.

The same observation will apply to a PORTAMENTO preceded by an appoggiatura. There are some artists who are unable to execute four consecutive notes without introducing one or two PORTAMENTI. This is a very reprehensible habit, which together with the abuse of the gruppetto, should be carefully avoided.

Before terminating this chapeter, wherein I have passed in review the most salient and striking defects engendered by a bad style, (duly pointing out, at the same time, the means of remedying the same), I pledge myself to return to the subject, whenever the occasion for so doing may present itself. Wrong habits are in general too deeply rooted in performers on brass instruments to yield to a single warning: they, therefore, require vigorous and perpetual correction.

Leave a Reply